The pipevine swallowtail, Battus philenor, is one of Florida's abundant swallowtails. It is also known as the blue swallowtail because of some individuals' coloring (below).

Follow Phillip

NomenclatureThe pipevine swallowtail was originally described by Linnaeus (1771) and placed in the genus Papilio with the other swallowtails. It was later moved to the genus Battus (Scopoli 1777). The name “Battus” is from Battus I, founder of the ancient Greek colony Cyrenaica and its capital, Cyrene, in Africa. The specific epithet is from the Greek word “philenor” which means fond of husband or conjugal (Opler & Krizek 1984).

Larvae of the pipevine swallowtail and those of the other swallowtails belonging to the tribe Troidini feed on plants in the genus Aristolochia and are commonly referred to as the Aristolochia swallowtails.

In the photos above, red larvae thrive on Elegant Dutchman's Pipe (Aristolochia elegans) which is anecdotally reported to be detrimental to pipevine swallowtail larvae, Scientific literature of the 1960s-80s found that invasive, non-native pipevines like A. elegans (aka calico flower) that have been naturalized in Florida were "deathtraps" for swallowtails. That no longer appears to be the case as the naturalized pipevines are so much more abundant than native pipevines in the 2020s. It appears that Swallowtails may have through natural selection found a way to survive these more toxic species of pipevines (more on that below).

Adults

The wingspread is 2 3/4-5 1/8 in. (72-132 mm). The dorsal surfaces of the wings of males are mostly black with blue or blue-green iridescence on the hind wings. The dorsal aspect of the hindwings of females has duller iridescence than that of males. There are light marginal and sub-marginal spots on both forewings and hindwings. The ventral hind wings of both sexes have blue iridescence and a row of seven bright orange sub-marginal spots. There is a row of white spots on the lateral aspect of the abdomen.

Above and below, Pipevine Swallowtail eggs on Elegant Dutchman's Pipevine.Eggs

Pipevine swallowtail eggs are reddish-orange in contrast to those of the related Polydamas swallowtail, Battus polydamas (L.), which are yellow or yellowish-orange. The eggs of all Aristolochia (troidine) swallowtails are partially covered by a hard, nutritious secretion that is usually laid down in vertical bands. There are numerous relatively large droplets on the bands. The secretion is produced by a large gland that lies above the female’s ovipositor duct .

Larvae

Full-grown larvae are approximately 50 mm (about 2 in.) in length.

First instar larvae have numerous short orange tubercles – each with a single seta. Second instars have longer tubules - each bearing multiple setae. The tubercles of third and fourth instars are proportionately longer, and the exoskeleton takes on a slightly glossy appearance.

Battus larvae commonly defoliate their host plants and need to wander in search of new plants. The elongated thoracic filaments of larvae have only tactile sensors and no chemosensory structures. These filaments and the lateral stemmata (eyes) appear to merely help larvae locate vertical objects, which must then be identified as host or non-host by the antennae and mouthparts. Wandering larvae may find new host plants by detection of plant volatiles. Aristolochia volatiles have been shown to be attractive to larvae of Battus polydamas.

Full-grown larvae are typically dark brown to black with sub-dorsal and lateral rows of bright orange tubercles, but some are red. In western Texas and southern Arizona, the red form predominates under conditions of higher temperature (above about 30°C). The factor(s) responsible for red larvae in the eastern U.S. has not been investigated.

Pupae

When full-grown, larvae (prepupae) wander off the host plant to find a pupation site. Pupation occurs well off the ground - usually on tree trunks or on cliff faces in the Appalachians. Larvae rarely pupate on green substrates . Before pupation they spin a silk girdle for support and a silk pad which they grasp with their terminal prolegs . After splitting the old larval exoskeleton and wriggling free, the new pupa hooks the cremaster at the tip of its abdomen into the silk pad.

Pupae may be either green or brown. Unlike pupae of other swallowtails, the sides of the bodies of Battus pupae are widened into lateral flanges. In the lateral views of pupae, the lateral flanges appear as bluish-purple ridges along the anterior half of the abdomen.

Green pupa and brown pupa of the pipevine swallowtail, Battus philenor. Photographs by Donald W. Hall, Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida.

Pipevine swallowtail larvae feed on plants belonging to the genus Aristolochia in the family Aristolochiaceae. Reports in the literature of larvae feeding on wild ginger, Asarum canadense. (Aristolochiaceae), knotweed, Polygonum (Polygonaceae), and morning glories, Ipomoea (Convolvulaceae), are probably erroneous and likely due to misidentification and to wandering larvae for the other plant species.

Aristolochia species are commonly known as pipevines or Dutchman’s pipes because the flowers of some species are shaped like tobacco pipes. They are also known as birthworts (“wort” is Old English for herbaceous plant) because of their historical use in child birth. The name Aristolochia is derived from the Greek roots aristos (best) and lochia (delivery or child birth). All Aristolochiaceae are believed to contain pharmacologically active aristolochic acids.

Although they are now officially banned in many countries, Aristolochia-derived herbal products or parts of the plants themselves are still used in many areas of the world for various conditions including snake bite, gastrointestinal problems, respiratory problems, wounds, infectious diseases, and fever.

Elegant Dutchman's pipe is perhaps the most common pipevine in Central Florida today. However, this plant species is non-native (from Brazil) and is sometimes reported to be toxic to Pipevine Swallowtail larvae. On most of my elegant dutchman's pipevines the larvae appear to be maturing to pupae, so while it may not be their most desirable host plant it likely is the most abundant.

Virginia snakeroot, Aristolochia serpentaria, has been used for many medical applications, and preparations made from it are still for sale online. An extract of the southwestern pipevine, Aristolochia watsonii, was the main ingredient in the snakeroot oil sold by traveling “snakeroot doctors” at medicine shows in the Old West during the 19th century. Aristolochic acids in the products have been implicated as causative agents of renal toxicity and also may be carcinogenic .

Aristolochia serpentaria, ranges from central Florida northward in much of the eastern United States. In the Southeast, it has broad-leaved and narrow-leaved forms. The broad-leaved form is more common in richer mesic forests while the narrow-leaved form is more common in drier, sandy areas.

Virginia snakeroot, Aristolochia serpentaria (broad-leaved form), a host of the pipevine swallowtail caterpillar, Battus philenor, with flower. Photographs by Donald W. Hall, Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida.

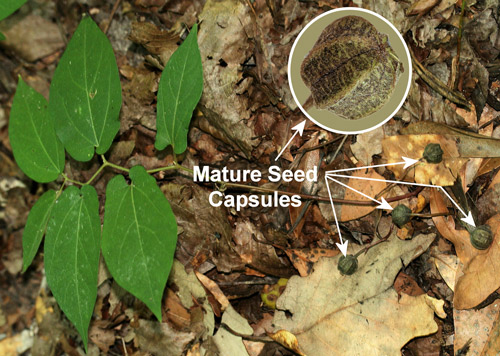

Virginia snakeroot, Aristolochia serpentaria (broad-leaved form), a host of the pipevine swallowtail caterpillar, Battus philenor, with seed capsules. Photographs by Donald W. Hall, Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida.

Virginia snakeroot, Aristolochia serpentaria (narrow-leaved form), a host of the pipevine swallowtail caterpillar, Battus philenor. Photograph by Donald W. Hall, Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida.

All Florida native species of Aristolochia within the range of the pipevine swallowtail are documented larval hosts:

Pipevine, Aristolochia macrophylla Lam. (synonym, Aristolochia durior Hill) USDA Plants Database species page.

Woolly Dutchman’s pipe, Aristolochia tomentosa USDA Plants Database species page.

Texas Dutchman’s pipe, Aristolochia reticulata Jacq. USDA Plants Database species page.

Watson's Dutchman’s pipe, Aristolochia watsonii Wooton & Standl. USDA Plants Database species page.

California Dutchman’s pipe, Aristolochia californica Torr. USDA Plants Database species page.

Aristolochia serpentaria and Aristolochia macrophylla (below) have been assayed for aristolochic acid, and both species were determined to contain significant quantities of aristolochic acid I. Because of their toxicity and distastefulness, the aristolochic acids play a major role in the biology of pipevine swallowtails.

Pipevine, Aristolochia macrophylla Lam. (synonym, Aristolochia durior Hill) a host of the pipevine swallowtail caterpillar, Battus philenor (L.). Photograph by Donald W. Hall, Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida.

Woolly Dutchman’s pipe, Aristolochia tomentosa Sims., a host of the pipevine swallowtail caterpillar, Battus philenor, leaf (left), unopened flower (middle), opened flower (right). Photographs by Donald W. Hall, Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida.

Elegant Pipefine is naturalized in Central Florida. Above, an Elegant Pipevine with my foot positioned bottom right for scale.

Deathtrap or Evidence of Evolution?Various exotic Aristolochia species are planted as ornamentals because of their unusual and sometimes beautiful flowers. Some of these may be too toxic (or too distasteful) for pipevine swallowtail larvae and may be “death traps” for the larvae.

Elegant Dutchman’s pipe or calico flower, Aristolochia elegans Mast (synonym, Aristolochia littoralis Parodi), is attractive to female pipevine swallowtails for oviposition, but literature in the 1960s - 80s reported that larvae usually did not survive on it.

Aristolochia elegans may be distasteful, but not toxic, to Battus philenor larvae. Some larvae may die due to starvation because of their refusal to eat it. Therefore, planting of Aristolochia elegans and other exotic pipevines are not recommended where Battus philenor occurs (central Florida and northward). However Elegant Pipevine is an abundant invasive species found in many Central Florida backyards.

In parts of Florida where Elegant Dutchman's pipe is the now-dominant pipevine species the swallowtail larvae appear to survive on the plant and survive to pupa despite the plant not being their native source of food. Perhaps over the past 40 years some swallowtails have selected to thrive on the abundant naturalized vine. Larvae appear to be concentrated toward the more tender new growth when found on Elegant Pipevine.

Pollination

Insect pollination

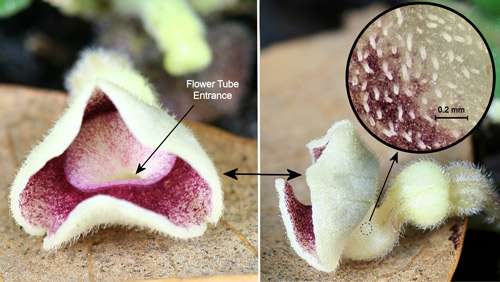

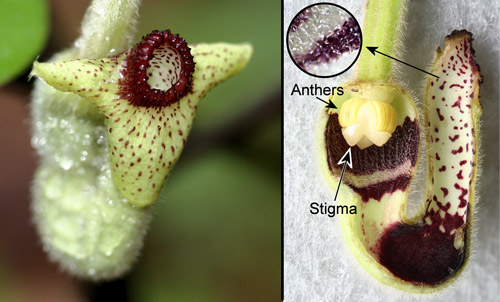

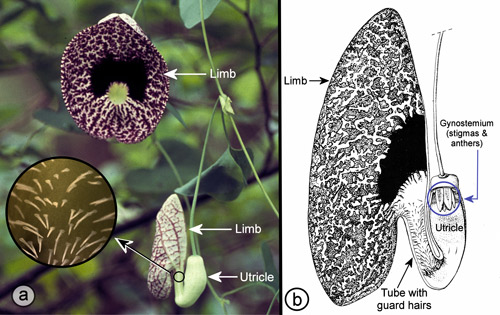

Aristolochia species have fascinating pollination biologies. When the flowers first open, the stigmas are receptive, but the anthers are not releasing pollen – a phenomenon known as protogyny (from the Greek roots "proto" [first] and "gyne" [female]). During the first day of bloom, the flowers are attractive to flies (usually small flies - often, but not always, scuttle flies in the family Phoridae) which enter the flowers carrying pollen from another flower. The flies are then prevented from leaving by the presence of downward projecting guard hairs or tiny spines and slippery surfaces in the tube of the flower.

Virginia snakeroot, Aristolochia serpentaria, flower: front view (left), side view (right), and inside of tube with slippery surface and small downward pointing hairs (inset). Photographs by Donald W. Hall, Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida.

Woolly pipevine, Aristolochia tomentosa Sims, flower (left) and longitudinal section (right) showing inside of tube with slippery surface and small downward pointing spines (inset). Photographs by Donald W. Hall, Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida.

Elegant pipevine, Aristolochia elegans M.T. Mast (synonym: Aristolochia littoralis Parodi). a ) flowers in front and side view orientations and downward pointing guard hairs (inset). b) drawing of longitudinal section of flower showing inside of tube with downward pointing guard hairs. Photographs by Donald W. Hall, Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida. Drawing by Margo Duncan.

On the second day (after pollination), the stigmas become non-receptive, and the anthers dehisce (open) dusting the flies with pollen. The guard hairs in the flower tubes wither, and in some species (e.g., Aristolochia gigantea Mart. & Zucc.) the flowers also droop into a more horizontal position releasing the flies that are now carrying the new pollen.

Cleistogamy

In addition to its open (chasmogamous) insect-pollinated flowers, Aristolochia sepentaria also has flowers that never open (cleistogamous) and are self-pollinated. The terms chasmogamous and cleistogamous are from Greek roots (“chasma” [open or gaping], “cleist”, [closed], and “gam”, [marriage]).

The cleistogamous flowers of Aristolochia serpentaria and their resultant seed capsules are little more than half the size of the chasmogamous flowers and their seed capsules . Also, the cleistogamous flowers do not have the characteristic “tobacco pipe” shape as they do not trap insects for pollination. Both cleistogamous and chasmogamous flowers often occur on the same plant. In contrast to the chasmogamous flowers, the cleistogamous flowers are often formed later in the season in some species and higher on the plant where those of Aristolochia serpentaria are more susceptible to being eaten by Battus philenor larvae.

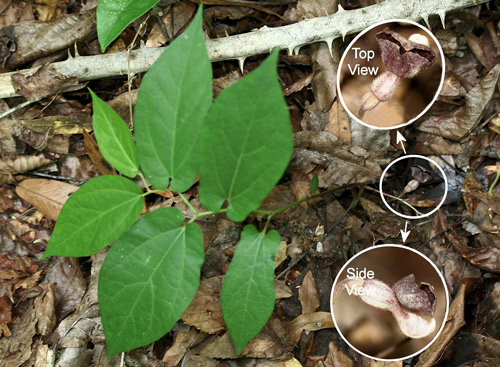

Virginia snakeroot, Aristolochia serpentaria L., plant with insets showing sequential stages of development of cleistogamous flower to mature seed capsule. Photographs by Donald W. Hall, Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida.

Nectar host plants

There are many plants that are valuable as nectar sources for butterflies. Pink and purple flowers (e.g., phlox [Phlox species], ironweed [Vernonia species], and thistles [Cirsium species]) are particularly attractive to pipevine swallowtails.

In my gardens zinnia are the preferred flowers of Swallowtails, especially in July and August. The zinnia are non-invasive and will die off in fall.

The Palamedes swallowtail (Papilio palamedes) may be confused with the Pipevine Swallowtail but it is not a mimic. The butterfly above does a dangerous dance with a lynx spider, but survives. The spider either finds the butterfly distasteful or too big to handle.

Swallowtail butterfly mimics of Battus philenor

Spicebush swallowtail (Pterourus [formerly Papilio] troilus) (Linnaeus)), (Papilionidae)

Eastern black swallowtail (Papilio polyxenes Fabricius), (Papilionidae)

Tiger swallowtail, (Pterourus [formerly Papilio] glaucus Linnaeus), (Papilionidae) – only the dark morph female is mimetic

Brushfoot butterfly mimics of Battus philenor

Red-spotted purple (Limenitis arthemis astyanax (Drury)) (Nymphalidae)

Müllerian mimicry in Pipevine Swallowtails

Eastern black swallowtail (Papilio polyxenes Fabricius), (Papilionidae)

Tiger swallowtail, (Pterourus [formerly Papilio] glaucus Linnaeus), (Papilionidae) – only the dark morph female is mimetic

Brushfoot butterfly mimics of Battus philenor

Red-spotted purple (Limenitis arthemis astyanax (Drury)) (Nymphalidae)

Female spicebush and black swallowtails have blue on the dorsal surface of the hind wings and appear to be more convincing mimics than males when viewed dorsally. Male spicebush swallowtails have light green and those of black swallowtails have a lot of yellow and very little blue. However, males of these species have orange spots on the ventral surface of the hind wings and are probably mimetic when the wings are closed. Under experimental conditions, male and female black swallowtails were equally protected when their ventral sides were presented to captive blue jays, but males were eaten more frequently than females when their dorsal sides were presented.

Müllerian mimicry in Pipevine Swallowtails

Müllerian mimicry is a type of mimicry in which two or more species are similar in appearance and are mutually distasteful or dangerous. Therefore, each species acts simultaneously as a model and a mimic and gains protection from the resemblance. Some researchers have suggested that Battus philenor larvae and certain millipedes may be Müllerian mimics. Some millipedes are dark colored like Battus philenor larvae and release hydrogen cyanide when threatened.

A garden full of butterflies wouldn't be complete without butterfly caterpillars. In these these kind of otherworldly images Pipevine Swallowtail Caterpillars (Battus philenor) feast on the leaves of Dutchman's Pipe Vine (Aristolochia elegans).

Below, in sunlight and shadows I think they look particularly alien.

Florida Aristolochia Species to Avoid

Many butterfly enthusiasts in Florida seek out Aristolochia (Pipevine) species to attract Pipevine Swallowtail and Polydamas Swallowtail butterflies to their garden. While their intentions are usually good, they often choose exotic Aristolochia species that are either detrimental to Pipevine Swallowtail larvae, or they choose an invasive species.

ARISTOLOCHIA SPECIES TO AVOID:

Aristolochia gigantea (Pelican Flower) – This species can be toxic to Pipevine Swallowtail larvae.

During straight flight, butterflies zip along at about 9½ feet/second (2.9m/s). During slower type of flight, the insects forage for nectar from flowers and fly in loops, with a speed averaging 5¼ feet/second (1.6m/s).

ARISTOLOCHIA SPECIES TO AVOID:

Aristolochia gigantea (Pelican Flower) – This species can be toxic to Pipevine Swallowtail larvae.

Aristolochia elegans (Elegant Dutchman’s Pipe; Calico Flower) (synonym; Aristolochia littoralis) – Common names for this species include Calico Flower or Elegant Dutchman’s Pipe. While Aristolochia elegans is palatable for both Pipevine Swallow and Polydamas Swallowtail larvae, this species is a category II exotic invasive in Florida according to Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council. Any plant, rather it is a category I or II invasive species, should be avoided. University of Florida’s Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants on the impact of Aristolochia elegans: “Calico flower has been shown to escape cultivation in many areas of the world, including Florida. It has the ability to weigh down native plants and cause collapse under of the mass of vegetation produced. This creates an opening for opportunistic weeds to invade and take over an area. When the winged seeds of Calico Flower are dispersed, they will germinate wherever they land. This species is difficult to control once established because of above and below ground stems and roots that require numerous herbicide applications.”

Aristolochia ringens (Gaping Dutchman’s Pipe) (basionym; Aristolochia grandiflora) – According to the assistant curator at Museum of Science and Industry (MOSI Outside) BioWorks Butterfly Garden Exhibit, Aristolochia ringens is toxic to Pipevine Swallowtail larvae.

More Butterflies

Flight With A Purpose

For at least a decade we've known that butterflies do not flutter aimlessly around the garden but instead follow precise flightpaths. Cant, Smith, Reynolds and Osbourne (Tracking butterfly flight paths across the landscape with harmonic radar. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 22 April 2005) were likely the first to use tiny tracking devices (harmonic radar) on butterflies.

Follow Phillip

|

| Gulf Fritillary (Agraulis vanillae) on Zinnia |

Prior to Cant et al. butterfly mobility had been predominantly studied using visual observations and mark-recapture experiments. Cant et al., by attaching light-weight radar transponders to butterfly's thorax proved that there is some method to butterfly flight madness.

|

| Polydamus Swallowtail (Battus polydamus) on Dotted Horsemint |

The images seen here are the best of hundreds taken over the course of a recent afternoon. Hundreds of shots revealed a few good, clear, images. The butterflies will not cooperate and sit still on a blossom long enough to get that perfect shot the first time.

|

| Zebra Longwing on Spanish Needles (Bidens alba) |

Straight Flight

Subsequent research indicates that butterflies exhibit at least two distinct types of flight pattern: fast, straight movement and slower, non-linear movement. During straight flight, butterflies zip along at about 9½ feet/second (2.9m/s). During slower type of flight, the insects forage for nectar from flowers and fly in loops, with a speed averaging 5¼ feet/second (1.6m/s).

Gone Loopy

It’s not just poetic alliteration that makes the pat phrase “a butterfly fluttered by” so appropriate. The insects, although not always that speedy, often take a flight path that involves so many erratic dips and turns that they almost look out of control. But it’s not because they can’t do any better: Such unpredictable flight is how butterflies evade birds and other predators. However, most butterflies are brightly colored, which would seem to counter their evasiveness by making them easier to spot and track.

Why do butterflies flaunt their visibility?

A butterfly’s ability to evade and its blatant pigmentation go hand in hand.

Flying in loops seems also to perform an orientation function, helping the insects identify flowers or hibernation spots.

Eisner and Jantzen (Hindwings are unnecessary for flight but essential for execution of normal evasive flight in Lepidopetera, Proceedings of the National Academy of Science vol. 105, no. 43, July 2008), explored this oxymoronic butterfly biology and found that the bright colors and patters along with erratic flight were survival mechanisms evolved to confuse predators.

Butterflies are able to identify and avoid unsuitable habitats such as dense trees from up to 218 yards (200m). They seem able to identify suitable foraging habitats from about 109 yards (100m).

Knowing how butterflies choose where to go and how they use and feed in the landscape is very useful to conservationists. . .to the photographer. . . not so much. Its is, however, fascinating that someone else has answered some of these questions.

Solving the Puzzles of Mimicry in Nature

A mimicry ring among African Butterflies

Perhaps no destination has attracted and inspired more great naturalists than Brazil. Charles Darwin, on his epic voyage on the H.M.S. Beagle, first made landfall at Bahia in 1832; two fellow Englishmen, Alfred Russel Wallace and Henry Walter Bates, arrived at Pará in 1848. Wallace roamed the Amazon for four years, and the indefatigable Bates for 11.

In 1852, a naturalist named Fritz Müller arrived from Germany. Much less known today, Müller, unlike his English contemporaries, moved to Brazil with his wife and young child and had no intention of ever returning to Prussia. A freethinker who refused to swear an oath to God required for his medical graduation, Müller traded a medical career in Europe for a mud-floor hut at the edge of virgin forest in the Blumenau colony in Santa Catarina.

While Darwin and Wallace would conceive of the theory of evolution by natural selection, its acceptance was aided greatly by Bates and Müller. And thanks to Bates and Müller, perhaps no group of animals contributed more to the early growth of evolutionary science than butterflies. Their ideas continue to inspire naturalists today and have led to surprising new insights into how evolution works.

Both men found Brazil ablaze with colorful butterflies. Bates noticed among his collections certain species whose bright wing patterns closely resembled those of other butterfly families in the area. In puzzling out why one species would mimic another, he realized that harmless butterflies were mimicking noxious species that were unpalatable to birds and lizards, and therefore not attacked by predators.

Only a few years after Darwin published “On the Origin of Species,” Bates suggested that this sort of mimicry — now called “Batesian” — was timely proof of the principle of natural selection.

While Bates was a full-time collector, Müller was initially occupied with more basic concerns. For his first few years in Brazil, he eked out a living as a farmer, raising chickens and pigs and trapping game, while enduring floods and fending off hostile indigenous tribes, jaguars and tropical diseases. As the only person in his settlement with medical training, it fell to him to attend to neighbors who had been impaled with five-foot-long arrows.

As his family expanded, eventually to six daughters, Müller moved to a coastal town to teach mathematics, natural history, and even some physics and chemistry. His position gave him a chance to explore more intellectual pursuits, and there he discovered Darwin’s new theories.

“Origin” so transformed Müller’s understanding of nature that he was inspired to write his own book, “Für Darwin,” that presented facts and arguments in favor of his theory, including Müller’s own observations on Brazilian plants and animals. The two men struck up a lively and warm correspondence that would last 17 years, until Darwin’s death. Darwin referred to Müller as the “prince of observers,” and although they never met, Müller considered Darwin a second father.

Müller’s crucial observation occurred after he returned to living in the forest. It was a new twist on mimicry. He noticed that unpalatable butterflies were also mimicking other species of unpalatable butterflies in the same area. If they were already unpalatable, he wondered, what added advantage was there to mimicking other species?

It dawned on him that unpalatable mimics would enjoy strength in numbers: Their unpalatability had to be learned by naïve predators, and mimicking species would share the cost of those lessons, whereas a uniquely patterned unpalatable species would bear the full cost. He showed through simple algebra that two or more unpalatable species would each gain an advantage through a common pattern.

Natural selection thus explained why different species’ wing patterns would converge. But how were such similar but complex wing color patterns generated by different species? That was a much more difficult question, and its answer eluded scientists for nearly 150 years, until an international team of researchers recently revealed mimicry’s innermost secrets.

The most striking and famous examples of what is still called “Müllerian mimicry” involve Heliconius butterflies in South and Central America. In many instances, the wing patterns of different species in the same area are remarkably similar. And even more remarkable, each species may exhibit several different wing patterns, each specific to a given area. The wing patterns are so similar that it is hard to tell species apart from even a short distance — and that is the point.

There are two fundamentally different ways Müllerian mimicry could evolve: Either each species independently evolved mutations that led to very similar wing patterns, or patterning genes were exchanged among species.

Several genes controlling the production of the wing patterns have now been identified, enabling researchers to distinguish between these alternatives. The answer? Both mechanisms have been at work.

By analyzing the DNA sequences in two mimicking Heliconius species distributed across South America, researchers could determine that each species had independently evolved up to 20 different patterns that were nearly identical in each species. But in more closely related mimicking species, they found that color-controlling genes had been exchanged.

These discoveries are equally interesting. It is astonishing that so many patterns could be independently generated and replicated in different species. And it is surprising to have species swapping genes in the Amazon. After all, the inability to breed successfully with other groups has long been an operational definition of species.

But as we peer into genomes, we continue to detect evidence of past interbreeding — between Darwin’s finches, for example, and even between Neanderthals and our own species, Homo sapiens. Even if such interspecies matings are rare, a gene that confers a strong advantage, like mimicry, can spread quickly through a population.

One of my favorite observations about scientific progress was offered by the Nobel physicist Jean Baptiste Perrin, who said that the key to any advance was to be able “to explain the complex visible by some simple invisible.” After being shrouded in mystery for more than a century, the revelation of the invisible genes that have generated such diversity is an exquisite example of the maxim.

Follow Phillip

No comments:

Post a Comment